Suffers of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) who were thinking about suicide showed clear differences on positron emission tomography scans from other participants in a newly published study. If the results are replicated in larger samples the work could help psychologists identify those at risk of suicide, hopefully providing opportunities to avert tragedy. More speculatively, the nature of the differences may offer a path towards new treatments that could restore the will to live.

We know depressingly little about the neuroscience of PTSD, but much of what we have learned has been quite recent. A Yale University team have previously identified a specific receptor in the brain, known as mGLuR5, as potentially being important, with higher availability in both humans suffering PTSD, and animals showing similar symptoms. Moreover, the up-regulation of mGLuR5 is particularly noticeable in parts of the brain that have been shown to be important to suicidal thoughts.

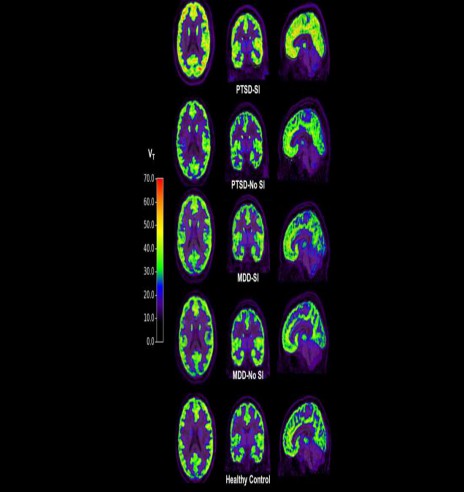

Dr Margaret Davis and other members of the Yale team compared 29 people with PTSD with another 29 suffering from major depressive disorder (MDD) and an equal number of mentally healthy controls. Half of both the MDD and PTSD group described feeling suicidal on the day the scan was taken.

Tests for depression are urgently being sought, but PET scans for mGluR5 are unlikely to provide them, as no noticeable difference could be seen between those with MDD, whether suicidal or not, and the controls. On the other hand, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Davis reports participants with PTSD had significantly higher mGluR5 availability in all five areas of the brain examined. The difference was entirely because of the subgroup of PTSD-sufferers experiencing suicidal thoughts that day, so that this subgroup stood out completely from all other participants.

The paper notes the study’s limitations – not only the modest sample size but the fact there was no test for severity of suicidal thoughts, which were instead treated as a binary option.

The findings have obvious potential as a diagnostic tool, helping psychologists identify those at highest risk. They could be even more valuable if it turns out an individual’s mGluR5 availability varies with time, depending on their psychological state.

However, the implications could be much more far-reaching, providing a potential target for drugs to control suicidal thoughts. There is increasing evidence that ketamine reduces suicidal thoughts. Clinical use is rare, though, not merely because of the drug’s illegal status, but because the reasons for its effectiveness are poorly understood. Ketamine is an antagonist of the NMDA-R receptor, which is moderated by mGluR5, so the picture might be becoming a little clearer.

Nevertheless, the authors acknowledge “The mechanisms by which mGluR5 may be upregulated… are not well understood.”