It is no secret that a bad mood can negatively affect how we treat others. But can it also make us more distrustful? Yes, according to a new study, which shows that negative emotions reduce how much we trust others, even if these emotions were triggered by events that have nothing to do with the decision to trust. The study was carried out by an international research team from the University of Zurich (UZH) and the University of Amsterdam (UvA).

That emotions can influence the way we interact with others is well known – just think of how easily an argument with a loved one can get heated. But what about when these emotions are triggered by events that have nothing to do with the person we are interacting with, for, instance the annoyance caused by a traffic jam or a parking fine. Researchers call these types of emotions “incidental”, because they were triggered by events that are unrelated to our currently ongoing social interactions. It has been shown that incidental emotions frequently occur in our day-to-day interactions with others, although we might not be fully aware of them.

Negative emotions suppress trust

For the study, UvA neuroeconomist Jan Engelmann teamed up with UZH neuroeconomists Ernst Fehr, Christian Ruff and Friederike Meyer. The team investigated whether incidental aversive affect can influence trust behavior and the brain networks relevant for supporting social cognition. To induce a prolonged state of negative affect, the team used the well-established threat-of-shock method, in which participants are threatened with (but only sometimes given) an unpleasant electrical shock. This threat has been shown to reliably induce anticipatory anxiety. Within this emotional context, participants were then asked to play a trust game, which involved decisions about how much money they wished to invest in a stranger (with the stranger having the possibility to repay in kind, or keep all the invested money to themselves). The researchers found that participants indeed trusted significantly less when they were anxious about receiving a shock, even though the threat had nothing to do with their decision to trust.

Disrupted brain activity and connectivity

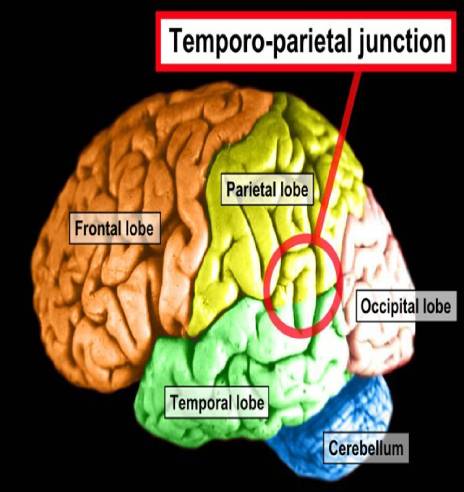

The team also recorded participants’ brain responses using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) while they made trust decisions. This revealed that a region that is widely implicated in understanding others’ beliefs, the temporoparietal junction (TPJ), was significantly suppressed during trust decisions when participants felt threatened, but not when they felt safe. The connectivity between the TPJ and the amygdala was also significantly suppressed by negative affect. Moreover, under safe conditions, the strength of the connectivity between the TPJ and other important social cognition regions, such as the posterior superior temporal sulcus and the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, predicted how much participants trusted others. This relationship between brain activity and behavior was nullified when participants felt anxious.

“These results show that negative emotions can significantly impact our social interactions, and specifically how much we trust others,” authors Jan Engelmann and Christian Ruff explain. “They also reveal the underlying effects of negative affect on brain circuitry: Negative affect suppresses the social cognitive neural machinery important for understanding and predicting others’ behavior.” According to Engelmann, their findings indicate that negative emotions can have important consequences on how we approach social interactions. “In light of recent political events in the UK and the forthcoming elections for the European Parliament, the results also contain a warning: Negative emotions, even if they are incidental, may distort how we make important social decisions, including voting.”

Abstract

The neural circuitry of affect-induced distortions of trust

Aversive affect is likely a key source of irrational human decision-making, but still, little is known about the neural circuitry underlying emotion-cognition interactions during social behavior. We induced incidental aversive affect via prolonged periods of threat of shock, while 41 healthy participants made investment decisions concerning another person or a lottery. Negative affect reduced trust, suppressed trust-specific activity in the left temporoparietal junction (TPJ), and reduced functional connectivity between the TPJ and emotion-related regions such as the amygdala. The posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS) seems to play a key role in mediating the impact of affect on behavior: Functional connectivity of this brain area with left TPJ was associated with trust in the absence of negative affect, but aversive affect disrupted this association between TPJ-pSTS connectivity and behavioral trust. Our findings may be useful for a better understanding of the neural circuitry of affective distortions in healthy and pathological populations.