The words you use betray who you are.

Linguists and psychologists have long been studying this phenomenon. A few decades ago they had a hunch that the number of active verbs in your sentences or which adjectives you use (lovely, sweet, angry) reflect personality traits.

They have painstakingly pinpointed various insights. For example, suicidal poets, in their published works, use more first-person singular words (like “me” or “my”) and death-related words than poets who aren’t suicidal. People in positions of power are more likely to make statements that involve others (“we,” “us”), while lower-status people often use language that’s more self-focused and ask more questions. Comparing genders, women tend to use more words related to psychological and social processes, while men referred more to impersonal topics and objects’ properties.

(This 2010 paper in the Journal of Language and Social Psychology goes into great detail about the “psychometrics” of words.)

This research suggests that Internet companies such as Facebook and Google, with their troves of written expressions, are sitting on powerful insights about us as people. But if you ask them, “Hey, can you give me the take on me that you’ve got in-house or that you’ve built for advertisers, with my anonymized data?” — they won’t give it to you. I actually did ask, and they don’t have that kind of offering.

But I’ve found someone who does: IBM’s Watson division. Researchers there have taken the personality dictionaries already created by scientists, dropped them into Watson (the computer that won Jeopardy!), and sent it off to apply it to people on Twitter, Facebook, blogs. That forms a digital population of people and personality types. Over time, more text from more people will help Watson get smarter. (Yes, this is machine learning.)

In its own studies, IBM found that characteristics derived from people’s writings can reliably predict some of their real-world behaviors. For instance, people who are less neurotic and more open to experiences are more likely to click on an ad, while people who score high on self-enhancement (meaning, seek personal success) like to read articles about work.

For IBM, these kinds of interpretations can become a business opportunity.

Understanding people to sell them things is obviously a very big business for marketers. IBM senior researcher Rama Akkiraju suggests other uses: by public relations firms looking for journalists who sound friendly on a specific topic; by editors who want their writers to set a certain tone; by employers looking for a worker who fits their corporate culture.

“We’re moving to make it easier for people to consume insights,” she says.

This use of Big Data, of course, raises serious privacy concerns, which we have examined in many stories. In this exploration, I decided to take a deep dive into Watson’s personal insights — what they can teach me about my career choices and my love life (yep, really went there).

You can listen to my story on NPR One.

Not all of the tools I used are publicly available, but you can try out a couple of them. Click on “view demo” here to test the tone analyzer that evaluated the tone expressed in my love letters. And here’s a tool to analyze personality through writing.

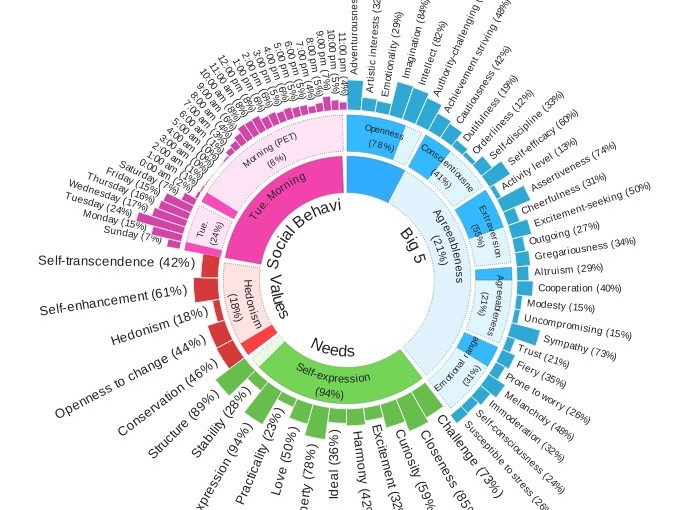

For now, Watson’s personality analytics is a work in progress and not easy on the eyes. The pie chart it spits out from a person’s social media posts, which you saw above, is a messy hodgepodge of about 50 traits. Plus, given how people curate their digital presence, the words we use online may be a highly biased indicator of who we are.

“It’s very interesting as a general curiosity,” says Sina Khanifar, a San Francisco-based technologist, “but what would really get me excited is if it made a particular recommendation.”

Khanifar says many tools exist to help you quantify yourself, track your running speed or breathing patterns. What few of them do is actually suggest how to improve your life. And, he says, people don’t just want to pay for insight. “When you go to see a therapist, it is about self-knowledge. But it’s also about a change.”

A friend recently mused about what this kind of tool could do for dating. People lie about themselves on dating sites chronically. What if Google developed a service to mine your mail and search and paired you with the perfect partner?

That could be amazing, or amazingly creepy.