Radar-like technology can see through walls to track the movement

As a child, Fadel Adib dreamed of having superpowers — like Superman’s X-ray vision. As an adult, he made this dream real by developing a way to use ordinary Wi-Fi signals to look through solid objects like walls.

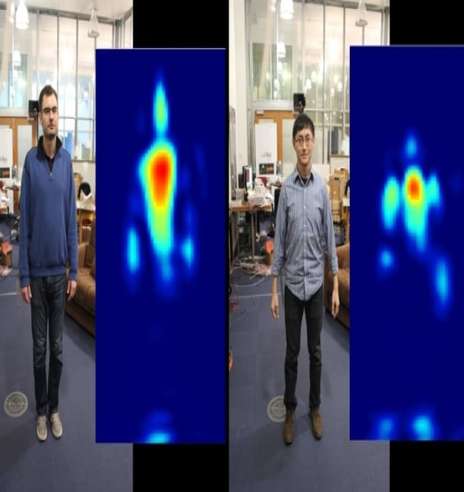

“You can see the person’s head, chest, arms, and feet,” said Adib. “You can measure even people’s heartbeats and emotions using these wireless signals.”

Adib thinks this technology could be used in a huge range of applications, from health-care monitoring to behavioral research.

The secret behind this development is something quite familiar — radio waves.

“Radios [waves] are very nice because they allow us to see the invisible,” said Adib, an assistant professor at MIT’s Media Lab in conversation with Quirks & Quarks host Bob McDonald.

The Wi-Fi router in your home sends and receives a constant stream of radio waves in order to connect to your smartphone, tablet or laptop. Adib harnessed this in a way that’s similar to another technology that can see things invisible to the naked eye — radar.

Discovering how to use Wi-Fi like radar

Several years ago, Adib was trying to understand how to increase the speed of Wi-Fi signals when he noticed something strange.

“Every once in a while, suddenly the data rate would go down and we would stop getting a good signal. And when we looked more into the problem we started realizing that there was someone who was walking on the other side of the wall,” he said.

It didn’t take long before he and his colleagues realized they could take this problem and turn it into a whole new way to use technology.

“When Wi-Fi signals travel in space, a large part of the signal reflects off the wall. A small part of the signal goes through the wall, reflects off the person’s body, and then comes back. So they carry this information about the environment.”

Their first challenge in isolating that information wall was to separate the weak signal from the person on the other side of the wall from the much stronger reflections off the wall and other objects in the environment.

“It’s almost like you’re looking at the sun and at the same time [that] you’re trying to see an airplane in the sky; the sun will blind you.”

Their solution was to transmit two signals, with opposite features, so that when these signals reflect off of stationary objects like a wall, they cancel each other out. Moving objects, like humans, didn’t reflect the same way.

“That allows us to cancel all the reflections of static things, but not of humans,” said Adib. “This is how we were able to start tracking people.”

Detecting fine-grained movements and emotions

Adib and his colleagues also started tracking more fine-grained movements, like the movement of the chest when breathing, or even the beating of a heart.

“What happens is that when your heart pumps blood, it creates a force and your entire body part starts to vibrate a very small amount with every heartbeat. And because we’re able to capture movements, we’re able to capture these small movements of your body and use them to get your heartbeats.”

It was a small step from this to being able to detect emotions.

“Your emotions are encoded and the variations between every heartbeat, and the heartbeat that is after it — so small millisecond variations between your heartbeats,” said Adib.

“If you’re able to capture these, then you can glean human emotions, like to know if someone’s sad, happy, excited or angry.”

A myriad of potential applications — and privacy risks

Adib said this technology is already in use in major hospitals across the U.S. to track disease progression in patients with Parkinson’s or multiple sclerosis.

“If you can track human movements and you will be able to detect disease progression over time or how the person’s movements are reacting to certain kinds of drugs to know whether the drug is actually being effective or not effective.”

Other potential applications they’ve explored include using the system as a baby monitor that could provide not just sound or images, but information about an infant’s vital signs. It could also be used to monitor the elderly so a caretaker could be notified if an elderly person has taken a fall.

The technology could further be used in behavioural research, to monitor how couples interact or caregiver-patient interaction.

But this technology also, clearly, comes with significant privacy concerns. Since it uses relatively conventional Wi-Fi hardware, use of the technology by bad actors to monitor people without consent is a risk the team has considered.

Adib said they’re working on developing countermeasures that would work much like anti-virus software to protect people’s privacy. But he says the onus also partly falls on legislators to be aware of these technological advances in order to put appropriate privacy-protecting policies in place.